When the residents of Camden, London were asked about a new high speed train line going through their hood, they had only two options : being for or against. A bunch of students at nearby Bartlett’s Interactive architecture Lab had a different idea: engage everyone in the vicinity to produce their own view of what the space should look like and make it accessible in VR. A great collective VR experiment for a near future where 3D scanners will be embedded in our phones.

The participatory approach of The Palimpsest reminds me of projects by the Assemble architects collective, who won the Turner prize last year. What were your intentions with this project ?

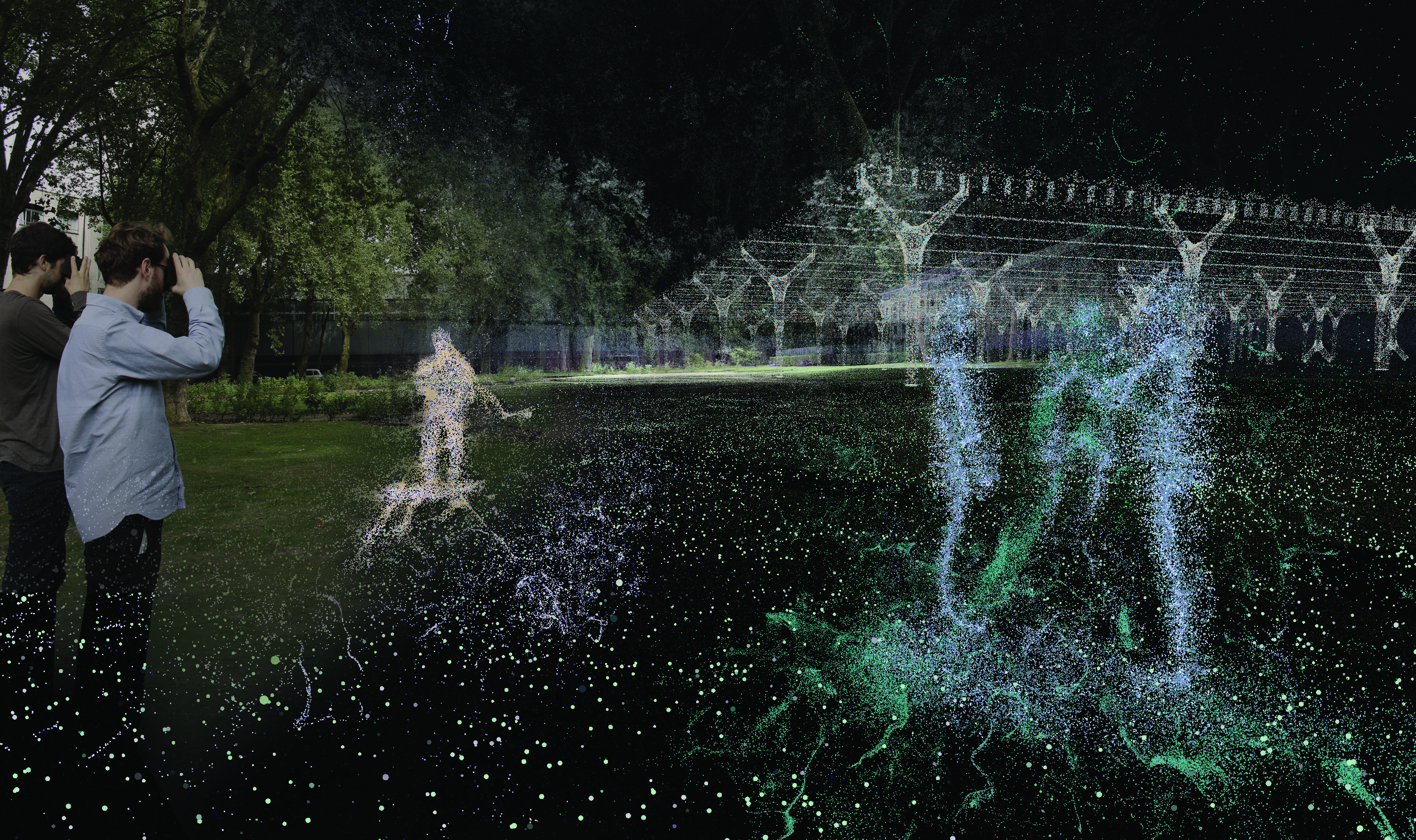

Haavard Tveito: We were exploring a lot of tools to see if we could make virtual reality into something more social, that could bring people together with a social agenda relevant to their city. Working on the project we realized it had to be site specific, much like MLF’s In The Eyes of The Animal started off as a site specific installation; so it’s no longer something to watch while you sit in your living room - it’s happening in the public space. In our case, we wanted to discuss public spaces not just as an isolating experience but we wanted this to actually be something that brings people together. Part of the project was also to create a tool for participatory design.

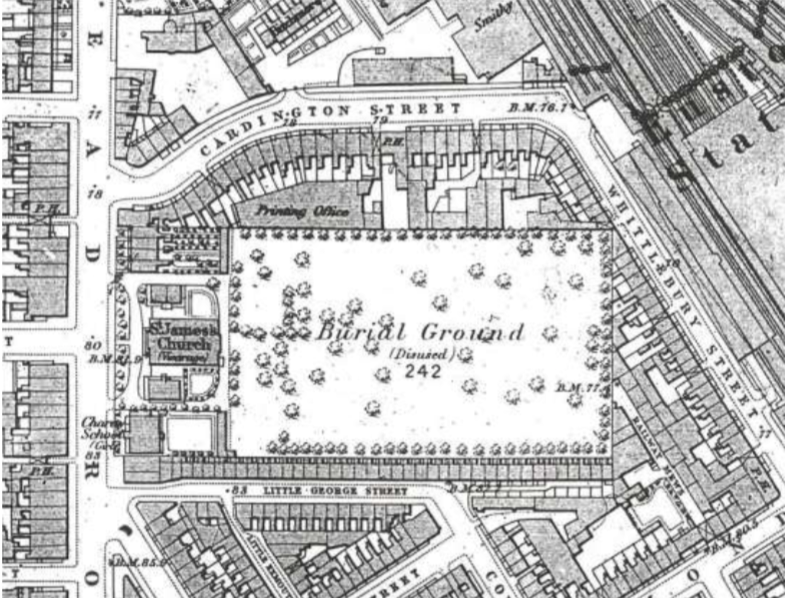

Russell Beaumont: Assemble, and also WikiHouse, are a some of people trying to get this bottom-up process going in architecture. We came across the Project Tango and the idea that 3D scanners were going to be in everyone’s cellphones in the next few years. It was really intriguing to us, especially as architects, and we were wondering what would happen when everyone starts to be able to take a snapshot of a 3D space; a room, a streetscape, or anything. As we were investigating this technology,we found out that a high-speed rail was coming through and was going to cause the demolition of some Bartlett architecture school buildings to make room for the new tracks. So with this interesting piece of technology catching our attention and a pressing issue of urban design that was happening around us, we started exploring how they might merge.

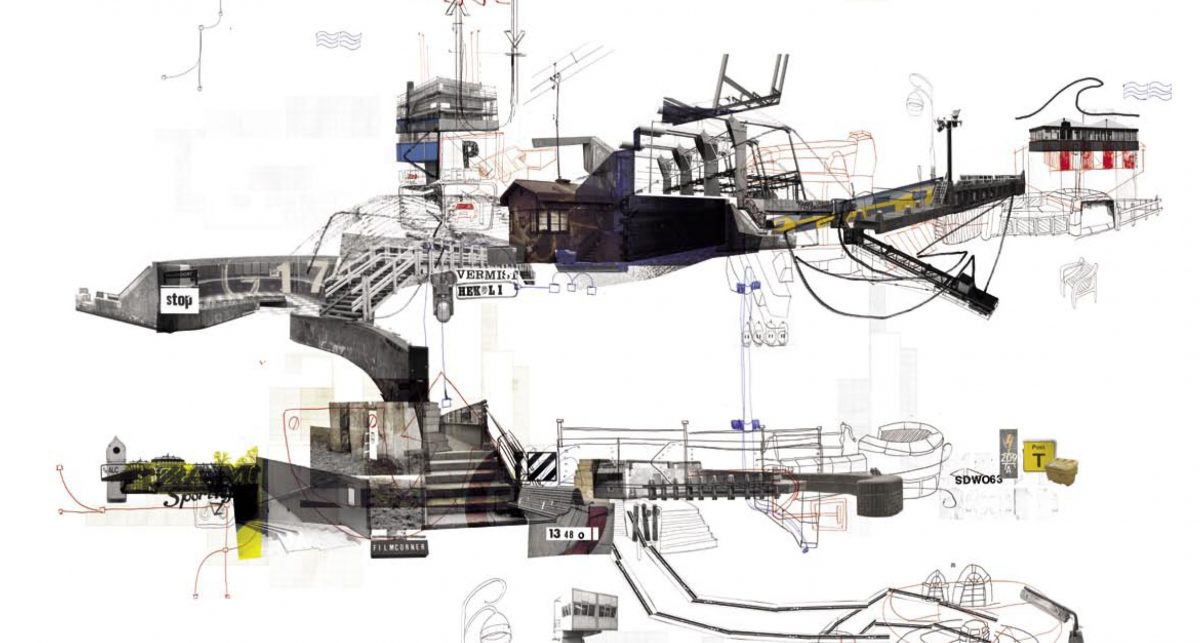

“What really intrigued us in the Project Tango is that any person can intuitively make a 3D model, and once you’re able to start recording the spaces, you can start merging them into a sort of a collage, you can start assembling them.”

RB: But you can also use it to interrogate a space that’s built. Let’s say a company builds a space, you can scan it and check it against what they proposed. And the preservation is another dimension to us. In the context of the high speed train project, a lot of people were talking about losing their homes, losing this or that. Suddenly with the Tango., you could have a 3D model inside of which you can actually walk and which could be saved forever. So this piece of technology was really interesting for us because we saw it fulfilling a whole range of needs that people might have in this situation where they are on the verge of losing their communities, their homes. From that point on, we had a lot of discussions about what the project would mean and how people would interact with it.

Empowering residents to build their city

RB: The current set up about how you would go and find out information about the high speed rail project was on the corporation's’ turf. You’d have to go in the building and talk with their representatives. So what we decided was that people could use this technology to 1, preserve and scan things that were important to them, 2 assemble it and merge together ideas, maybe making a collage of a space as they’d wish to see and 3, give official proposals a tangible feedback in VR. We envisioned all three of those things being physically located in public spaces, in a public park. That way you can go to a public space, you don’t feel like you’re intruding, you don’t have to go inside a corporate building and talk to someone who’s going to try to convince you. It’s your space. That’s why when you go into the VR experience, you see that park around you. You are not just there because it’s pretty, but because it’s right next to the station and will undergo many changes. It’s a big open space that is well used; people are eating there, hanging out there constantly, so we wanted to introduce the public debate there.

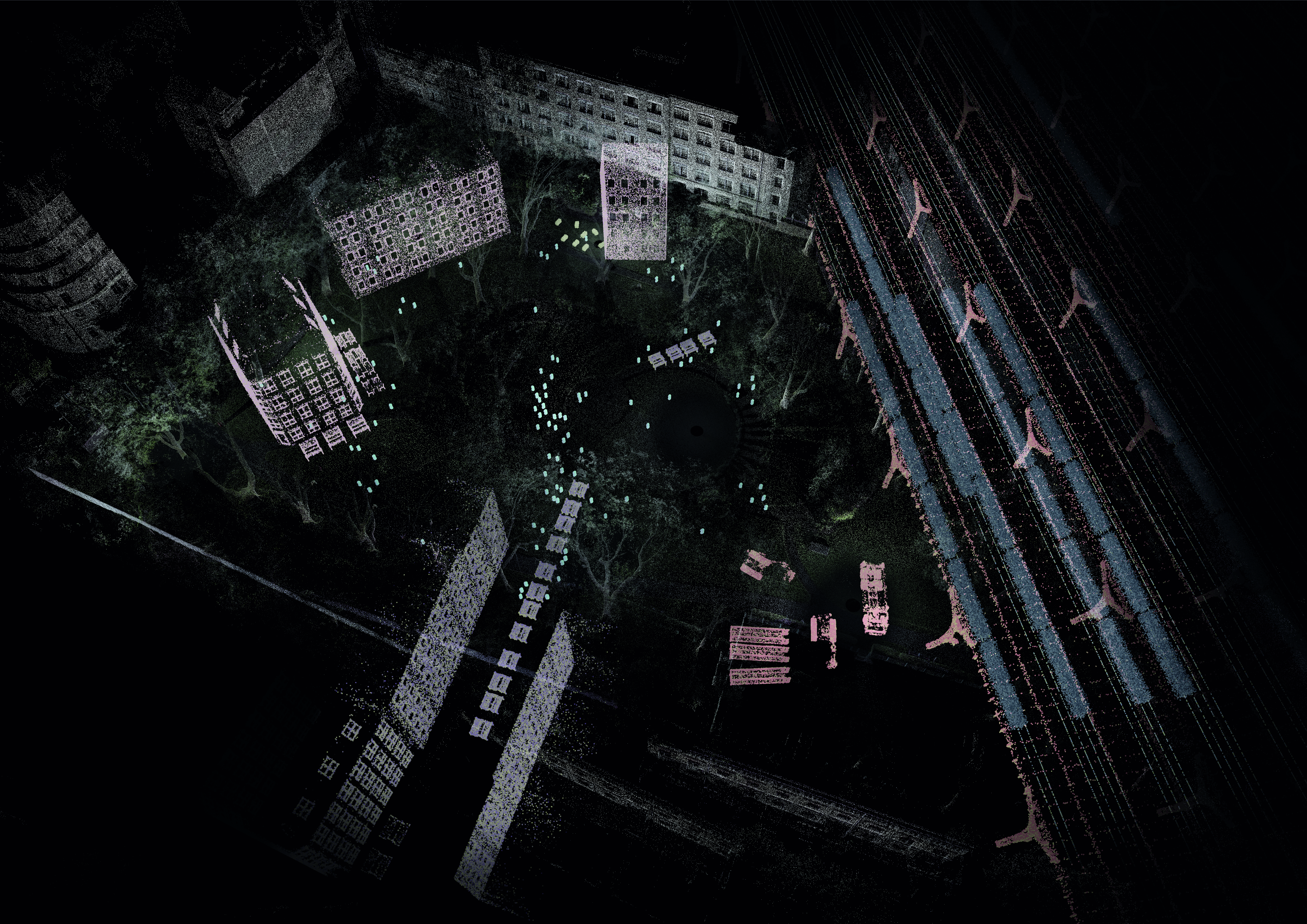

HT: We also wanted to use the potential of virtual reality in the sense that you are no longer stuck to having representational models; when discussing urbanism you often see a birds’eye-view of models, from above looking down, and extremely abstract drawings.

With virtual reality, you find yourself one to one in the space; you really feel like you are present. It becomes a medium where you have other senses involved than just your vision.

We also used sound to tell these narratives. In a way it can become like a collective memory. I wouldn’t go as far as saying that it becomes a collective consciousness but it has the ability to become a collective memory of the spaces that we lost, besides being able to anticipate what will happen in the future.

It made us think about the collective memory of music festivals. A place might radically change for a week and during the year it could become a collective memory in a way, but also the anticipation of what’s going to happen. It’s a play on these ideas but it will become a lot more tangible because it’s difficult to have a memory of a space that becomes lost, especially sonically.

HT: Virtual reality can keep that memory and restore it but also, going back to the idea of why we chose the name Palimpsest is that this will become an archive that could be written over and over. So you don’t have one correct truth; it will be overlaid over time and that way can become an archive of how our cities evolve on a larger scale. It may give us a knowledge that is very hard to obtain if you only have a snapshot, photographs or drawings that never give you the full idea of how this functioned.

From antiquity to VR, Palimpsest as the practice of layering time over spaces

How does the notion of Palimpsest apply in your work ?

RB: The word palimpsest comes from historical studies. Medieval scribes would scrape off the surface of parchment paper and rewrite over it because it was very expensive to produce. And because it was made of goat’s skin, it lent itself to that. Using X-ray technology we are now able to read what was written on each layer. For example some Archimede’s truths have been found under Bible writings. They discovered some new mathematical truths a thousands years after being written. It’s really fascinating.

RB: Palimpsest is also a term in architecture. If you’re ever in an old building and you look at the archways that are filed in, you can read how there used to be a door or a window that is now a wall. It gives you a glimpse into the history of the building but also a tangible, concrete: “this is what the building is now” but you can look closer and read into its past. We were very intrigued by how this concept plays out today, especially with the digital technology like Github where you have this sort of palimpsest forming, where the new ideas are branching out and even though there this end product that’s forming, there is all this depth to it and all these different ideas that were inside of it.

HT: We thought it would be excellent for communities to interact with urban developers this way. Allowing the memory to form, as much forming new visions we’re moving towards. People could layer their ideas, making proposals: “I want a project like this or this, I want the train tracks to go there or there.” You can read all that digitally and you can see a sort of render a hard rendered final version, or experience it physically if it’s built.

A reality powered by its multiple possibilities

It’s fascinating this idea that a reality is made of all its possibilities. So you intended to provide an experience that would show all these layers of “possibles”?

HT: Yes it’s not one clear narrative. We want to create a canvas or a level playing field but in some ways it should be “unpure”, it should be about conflicted ideas. What we are seeing in the public debate is that the only stance for the public is to be for or against a proposal. We see this quite a lot I think, there isn’t a possibility to offer alternatives.

“The only stance for the public debate is to be for or against a proposal. there isn’t a possibility to offer alternatives.” Haavard Tveito.

: I want to refer to the amazing piece of critical art by this group of American artists, The Yes Men, who made a complete, fake version of the New York Times announcing that the war in Iraq was over. They printed out hundreds of copies and handed it out on the street. It was a spoof obviously but it pointed out how far we were from the possibility of ending the war. If we can’t even imagine that the war can end, how can it happen? The Yes Men took the stance that you have to plant the idea, to seed it. Likewise for city planning, you have to introduce the idea that an idea is possible. Ultimately, we all have a say in how we make our cities, whether we are designers, urban planners, architects or a citizen, it shouldn’t really matter.

RB: We wanted people to offer their own alternatives, to say: “Here is my favourite pub, let’s preserve it” or: “Here is my mash up of all my favourite train stations in England; couldn’t we make the new one look more like this?” So we wanted to be constructive and also propose an alternate story in a very concrete and tangible way, adding people’s different relationships with urban development in a spatial context.

Thinking spatially, an ability to distribute more evenly

RB: There is this barrier of thinking spatially. As architects, we go through years of training to do that, but it’s intimidating to people. Whenever I go to a new building with friends they say : “tell me if it’s a good building”. My answer is always: “You tell me! 99% of the world is not architects so your opinion is more valuable than mine.” We want to push through that and get people thinking: “I can understand space, I can mash it together, I can tell you whether I’m happy or unhappy”. That’s what you can do with VR, 3D scanning, Photogrammetry, 3D software, using a Kinect to record 3 dimensional video. We wanted to use low tech, easy, cheap technologies that we could find to make it more accessible, to get people thinking spatially about how they could participate and contribute in the discussion about urban space and the city.

What are the tools that you put into people’s hands?

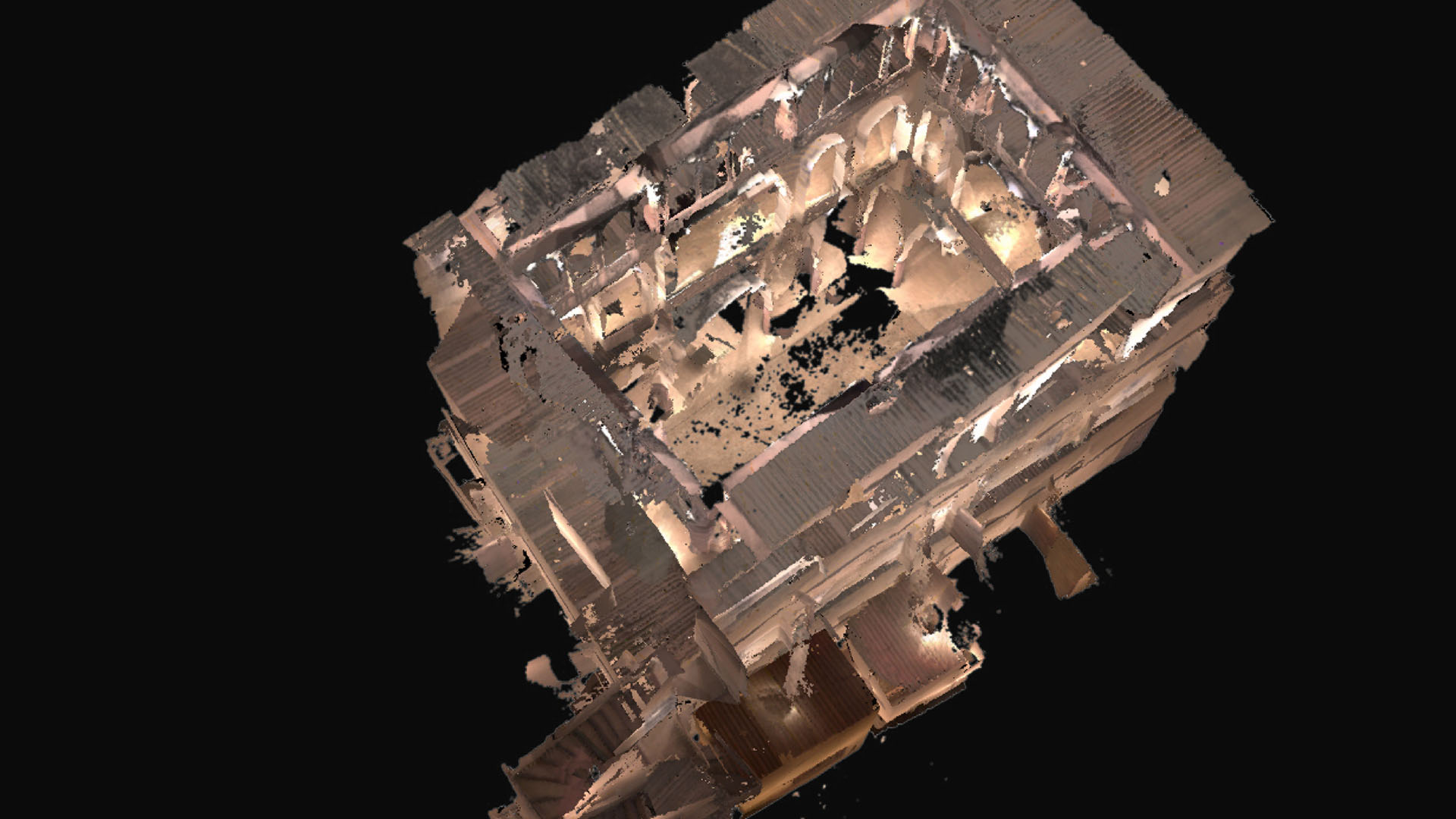

HT: We were mainly using the Project Tango for its scans. We did end up a LiDAR scanner for the environment, the park, because it was such a large space. While this is not accessible to the general public yet, there are already libraries of free LiDAR scans.

RB: We also used binaural sound. We recorded three-dimensional sounds by simply using microphones inside our own ears. It became an extremely simple but effective way of capturing the ambience in the space, with really quite cheap microphones and sound recorders. We worked further on trying to bring it to the digital side and processing it more but the idea is that when people would do scans they would have a Project Tango microphone connected to their mobile phone. You could really get a sense of the space and the situation. In some ways it links back to situationists creating this collage of the city. But it becomes a lot more effective when you actually can experience it, when it’s not only a conceptual piece, a drawing on a piece of paper, but where people can contribute all together.

On the nature of the spaces that are created by the Tango, which aren’t perfect which are full of glitches, they do contain something that seems fairly exceptional. How would you qualify that? What do we really experience when we experience these spaces?

HT: There is an ephemeral quality to it and there is also openness to them. I think the imperfections are extremely important. It’s really anti modern, it’s really lived in. It’s against this Mies Van Der Rohe idea of a window blind that could only open three ways so the building would always look perfect from outside.

HT: It’s very different from the way architecture is more and more portrayed in the media and even the way people are portrayed in the media. It’s all photoshopped, it’s all perfect. By capturing all the imperfections it becomes more real, in a way, that what we might experience in other mediums.

Photorealism working against perception

RB: One thing that both Tango and LiDAR did also are point cloud environment. One of the reasons we were drawn to this messy, almost transparent, ghostly, smoky environments was that people, when they get inside of those, start to focus on the space, on the sound, on the interview that’s happening. We found that when you do a rendering where there are cinder blocks or wooden floors, people say: “I don’t like cinder blocks, I don’t like the color of the wooden floors”. They start focusing on those details. But when it’s this ghostly suggestion of a room, they start looking around the room and feeling the space. So for us to be pushing that kind of messy environment was also a way to get people to focus more on the content, to fill in the gaps with their minds and not concentrate on how real it was or how fake it was, instead focusing on the concept of the space and what was being proposed.

Thank you guys for your insights and work, we’ll continue our journey into VR and architecture in a next episode.