- FR

- EN

In this second entry of the developers’ diary, Fabbula explores DRIFT’s narrative process: how the game tells its own particular story, while doing much more than simply framing the gameplay.

Along the way, we discuss transhumanism, the cognitive power of social networks, and the concept of AI as a credible narrative partner in VR. Read on!

The activating spectator at the heart of conception

If the principle of an omniscient camera, able to move around freely, is a staple of modern gaming, in DRIFT the player’s point of view is the camera, and vice versa. It is our point of view that builds the game’s action, determines success or failure, and tells a particular story.

The goal is for Sharpsense to offer a never seen before gameplay mechanic: looking for the right trajectory, while keeping one’s eyes in the right direction. A hark task for a tricky gameplay: even by tinkering with our phone’s clocks in order to play with unlimited slow-mo, finishing the game was certainly not a walk in the park.

Moving beyond its innovative gameplay, DRIFT is a game that explores and questions the tropes of gaming. Particularly, it underlines the importance of point of view in gaming and in VR. It is what unites both these mediums: in both cases, it is the spectator that actively takes part in the work, by interacting with the image he sees and, in turn, creates. We could talk of an “activator” of the whole experience. In DRIFT, one must quite literally “work” on its point of view, instead of relying on eye-hand coordination and reflexes.

Starting from there, the developers had quite a bit of fun. We constantly shift from overall shots to close ups; level design relies at first on fixed environments, then it starts moving and shifting.

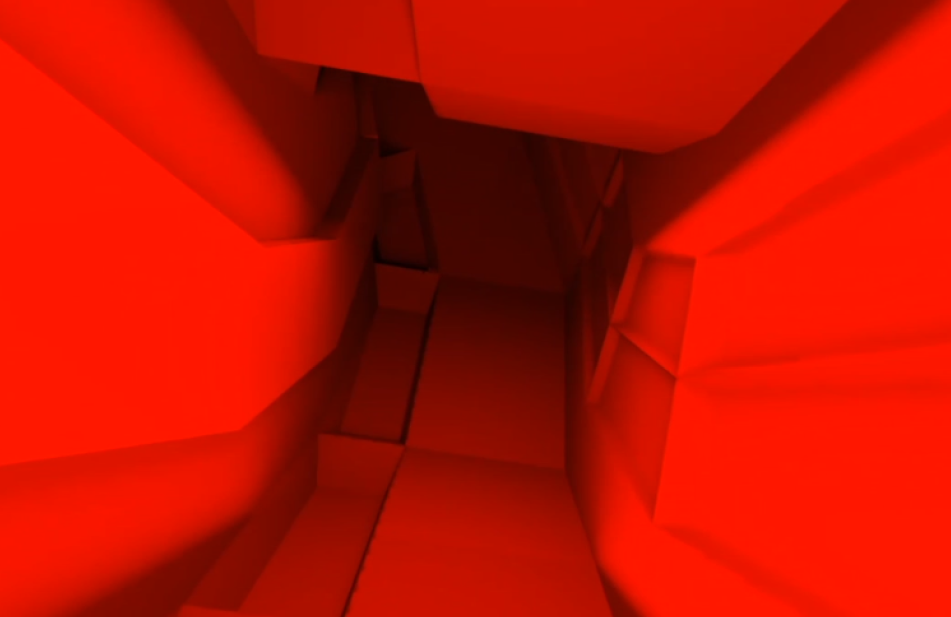

Some levels start turning, others glitch, and it is again the relationship between the player’s point of view and the environment that is deeply explored. The abstraction is more and more pronounced and stimulating. We play in our own head, in a long forward traveling, in which our visual concentration shifts between a focused, tunnel-like one and a peripheral one in search of alternate courses.

Cutscenes and dialogues, a Video walkthrough

With a game as enthralling – and difficult – it would have been easy to lose sight of the story – told by our in-game guide Walter – which unfolds through intertext and in cutscenes before each level. However, these cutscenes are as many narrative gems which reward the player who made it this far. They deliver a rich story in a refined fashion, written by screenwriter Maxime Phedyaeff.

By working the interludes as cutscenes between levels and with intertext – that is, mostly Walter’s comments if the player loses its way (which happens fairly often), the designers brought a dimension that questions our very presence in the game and our perception of its goals, as well as an underlying critic of gaming and VR in general. We explore this in the video below:

Level 1 - Virtual perfection

Everything starts with the first cutscene, in which we are introduced to the game as a simulator of perfection, a concept imagined by one Dr. Kwong, whom Walter, the narrator, serves. The endgame seems to be to upgrade our psycho-motor capacities in order to be able to defend ourselves against sophisticated foes. Those range from conventional gamey characters, such as samurais and zombies, to real-world inspired alter-egos, such as terrorists or hipsters.

It is a way in which the real emerges within the virtual (the game’s own conception coincides with the first wave of terror attacks in Paris in January 2015), and immediately reveals that this story will be told on several levels.

Level 5 - Military-industrial complex and octopussy intelligence

As levels progress, particularly after the difficult fourth level, and as the game reveals a demanding gameplay, we discover a story that reads like a hidden discourse on VR, the player’s role, and on the idea of interactive narration.

In the fifth level, we learn that Dr. Kwong, the creator of this simulator of perfection, has worked with military agencies and experimented on octopuses. A wink at the too-easily forgettable links between military funding, research laboratories, and new technologies?

Level 6 - Tilt fun

The sixth level reveals the role of the game’s designer and his creative adventures. In the end, it looks like the inspiration came from a baseball pitch, in which the player would play as the ball. Ouch, this is gonna hurt! And indeed, the game takes place in an arcade flipper, and we are a ball battered between the bumpers… It certainly isn’t the easiest level!

Level 7 - Acorns for a hero

In the seventh level, Walter gives us an acorn (our name being Mr. Squirrel) and predicts us a destiny as a superhero, before shoving us into a superb action movie scene, complete with special effects and numerous protagonists. We notice that this is the first truly animated scene: the slow particle movements reinforcing the dramatic tension.

Level 8 - Inside the whale

Later on, we learn of a special helmet that grants the ability to talk… with an octopus. The very shape of the helmet is reminiscent of what we are actually wearing. Walter offers to communicate with a whale.

It is some serious future work for VR, communication with animals. Walter wonders whether this reveals an emotional deficiency from the designer. We’ll have to investigate the whale’s belly in order to find out – cue the reference to Jonah, Moby Dick or George Orwell´s essay perhaps.

Level 9 - Glitchy ruins

The ninth level is one of my favorites, and draws a parallel between the romantic beauty of ruins and computer glitches. Indeed, Walter offers for us to play an old level from his archives that appear to be damaged. It simply is the first level of the very first version of DRIFT (link to DRIFT VR Jam), a familiar environment for the first players of DRIFT on gear VR.

The only difference is that this version has become unstable and moving, and that obstacles appear and disappear without pattern. It is very hard, but a nice way to offer a new take on our own gaming memories. It’s also the occasion to underline that an entire generation was born with mass personal technology, and that nostalgia today has its roots in networks and machines. What happens when these archives are stocked in a data bank belonging to Facebook, Google or another web site operating according to the principle of valued creation for the stockholders?

Level 10 - AI in a box

Level ten questions Walter’s identity. Who is he exactly, if not the thinking matter of a box that seems replicable? Is he really only an AI, since he seems so attached to his emotion and his own identity?

This is a direct reference to the power of machines and of AI to tell captivating stories. It’s also the occasion for DRIFT to recall that every new medium gives way to new expressions, and the possibility to tell new stories.

We can date back the concept of procedural narrative to the 60s, with experiments like Eliza, a virtual conversation program developed by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT in 66. A very effective storytelling machine, as described by Janet Murray in her essential essay Hamlet and the Holodeck: “To Weizenbaum’s dismay, a wide range of people including his own secretary would “demand to be permitted to converse with the system in private, and would, after conversing with it for a time, insist, in spite of Weizenbaum’s explanations, that the machine really understood them”.

With the rise of VR, what are the stories that we are now able to tell? Or, to use the words of filmmaker Werner Herzog: “Does virtual reality dream of itself? Do we dream or express and articulate our dreams in virtual reality?”

Level 11 - Recursive machines

In the eleventh level, we discover an environment made of boxes that look like the one that contains Walter’s AI in the tenth level. It leads to a questioning of our own identity. Are we Walter? Are we the designer of our own experiences? Who is the author, and who is the player? The player then loses himself in a vertigo of questions and sensations.

Beyond this framing device, the question of the border between machine and human, player and author, is at the heart of modern preoccupations. Since the start of transhumanist thinking in the 80s with Donna Haraway, the stories told by the new media account more and more for porous or even non-existent boundaries between notions that were traditionally opposed. Indeed, there are quite a few ways to decrypt DRIFT´s cutscenes…

Level 12 - VR as brain download

In the prelude to level twelve, Walter warns us against the human to animal communication system designed by Dr. Kwong – the infamous helmet that looks like a Rift. Is it a two-way system? Is Dr. Kwong capable of reading the human brain, and plant information in the octopus?

Level 14 - A Space Odyssey

Level 13 muses about octopussies and level 14 simply see us float in the cosmos…

Niveau 15 - Resolution

Finally, the fifteenth level explains it all. I will let you discover for yourself where all of this led.

Level design, or the setting of progression and difficulty

“We have to throw the stone as far as possible. It’s by exploring and experimenting with the limits that we can map out what’s in the realm of possibilities.”. Ferdinand Dervieux

In the initial version of DRIFT, the 4 levels were simply connected by a shared space and the elevators from which our character seem to emerge. The progression and the rise in difficulty was also very steep, level 4 being almost unbeatable. By the way, if anybody ever beat level 4, please send us the video of this feat, so that we can shower him with glory.

In DRIFT’s final version, the gameplay was set to have the same progression and to reach the same difficulty, but spread over 15 levels. We start off much easier and then rise to the challenge much more progressively.

This doesn’t stop the game from being difficult, even very difficult. This could explain why many have missed the game’s qualities and depth, or even its core message. At Fabbula, we sometimes feel we’re the only one to actually have finished the game. In any case, there is probably few VR gamers experienced enough to embark on such an adventure.

And of course, as every other aspects of the game, the difficulty is something Sharpsense completely owns up to. They even talk about it with a mischievous look…

Because this is of course a narrative choice from Sharpsense. This blends in with the game’s radical aspect that we discussed: this simulator of perfection, and its general commentary on modern context.

Even the name of their studio is revealing: Sharpsense. Furthermore, we can infer that the game’s intertext, as well as the images coming in the press kit (screenshots that most player could never connect to the game’s contents) and the basic communication on the game itself, reinforce the idea of difficulty in game, and out of the game world too. Talk about the art of extending the game’s domain out of its active moment!

In the next and last entry of DRIFT creation journal, we will explore the art direction of the game. Stay tuned by following us on facebook or twitter!

A few weeks after the game’s release, Sharpsense did start communicating on the unlimited use of Slow-mo on Saturdays. And some of us, used to that kind of gameplay, realized that by setting our phones’ clocks on Saturday, we could use unlimited slow-mo at all times. But don’t tell anyone.