Theo Triantafyllidis:

Live Simulation

an essay by Domenico Quaranta

In the context of the exhibition Among the Machines, Fabbula commissioned a series of essays in collaboration with the Zabludowicz Collection, exploring worldbuilding practices, new virtual ecologies and alternative metaverses.

For the first chapter, we invited contemporary art critic and curator Domenico Quaranta to delve into the practice of artist Theo Triantafyllidis.

Among the Machines was on view at the Zabludowicz Collection from March 24 to July 7, 2022. The essay is part of the exhibition catalog available on the Zabludowicz Collection online store.

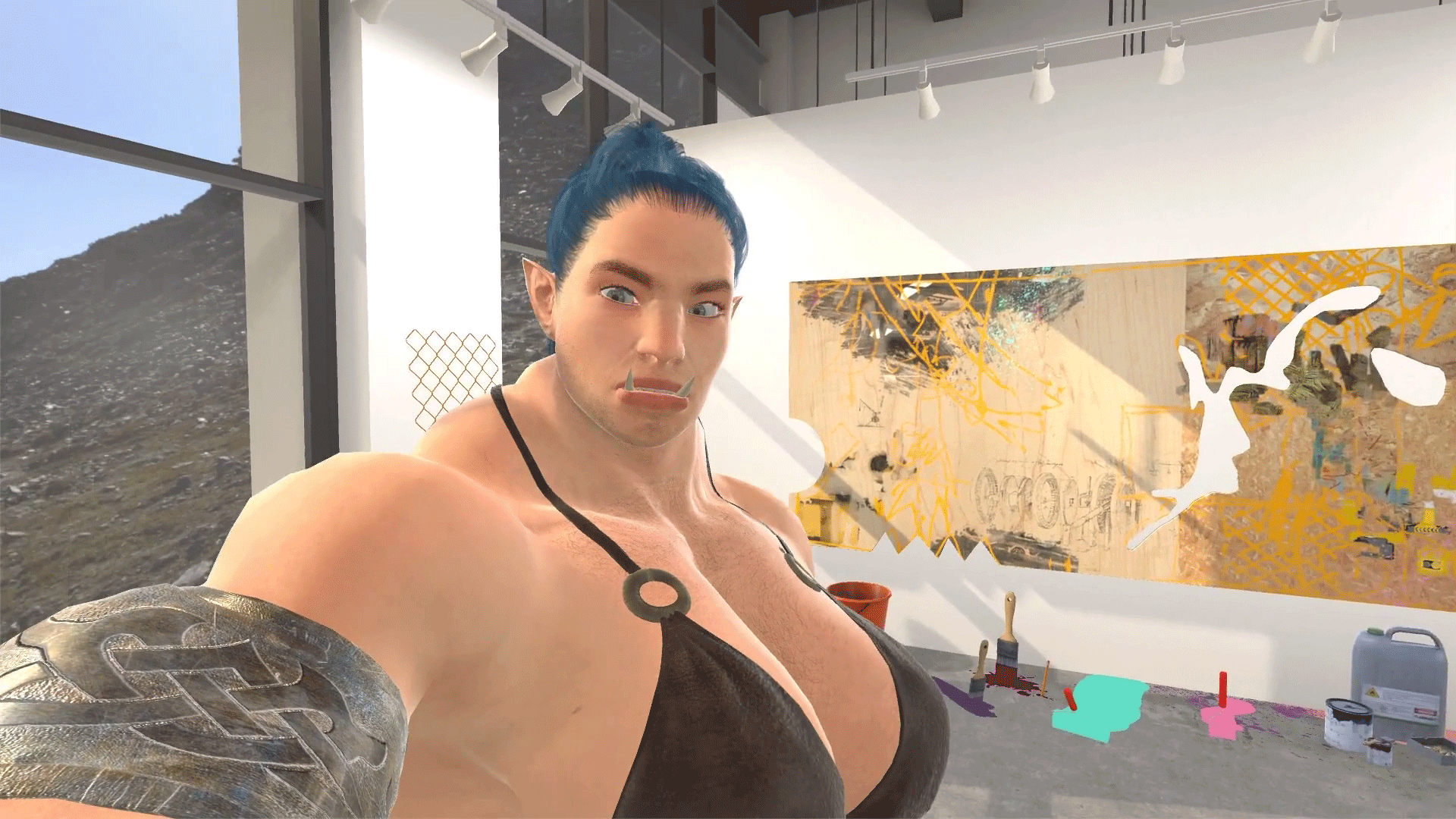

Theo Triantafyllidis, Painting – Preview, 2018.

‘OK, I’m gonna be honest with you: I don’t get painting,’ the brawny, blue-haired Ork says to the camera. He is wandering around a conventional studio space, with a prepared plywood board on the wall behind him. I’m using the male pronoun, but the fantasy character is in fact wearing a bikini, and sporting both male and female physical attributes. ‘Like, why would people wanna paint today? […] You know, this medium has such a great history but, you know, why do it … right now?’ To get to grips with painting, the Ork starts making gestural brushstrokes and dripping colour onto the board before adding objects and – ‘as I’m supposed to be a media artist’ – a plasma screen to it. Ork formalism: brutal yet accommodating at the same time. [1]

The Ork is controlled by the artist’s body (via motion capture), speaks in his voice (slightly altered) and creates the works on show.

Triantafyllidis’ ironic commentary is not so much on painting in general; it is targeted at modernism and the survival of modernist painting in the post-digital age. Yet I feel this piece works not only as a joke on ‘how you can get to simplicity either by extreme sophistication or by sheer stupidity’, as the artist put it in an interview [2], but also as an introduction to what appears to be one of his favourite media so far: the live simulation.

Theo Triantafyllidis developed the Ork character in 2018 as his own avatar for the exhibition Role Play at Meredith Rosen Gallery in New York. In the virtual space of the studio, the Ork is controlled by his body (via motion capture), speaks in the artist’s voice (slightly altered) and creates the works on show (the aforementioned painting, as well as sculptural assemblages of 3D objects printed on plywood cut-outs and installed in the physical venue). The exhibition thus becomes a mixed reality experience in which the real space awkwardly doubles the virtual space of the studio inhabited by the Ork, which is ‘performed’ on a few large screens on wheels.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Studio Visit, 2018.

Site Specific Mixed Reality Installation.

At the very beginning of modernism, Edgar Degas reportedly wrote: ‘The frame of a painting by Mantegna contains the world, whereas the moderns are only capable of rendering a tiny corner of it, a mere moment, a fragment.’ [3] In a world accelerated by industrialisation and fragmented by the advent of photography, and witnessing the change from painting as the main mode of artistic representation, modernist painters focused on the instant and increasingly, as Clement Greenberg pointed out, on the medium of painting and its material qualities: the shape of the canvas, its flatness, the pigment, the brushstroke.

Most live simulations effectively re-enact and build on the classical genres of Western tradition: the still life, the landscape painting, and the historical, religious, mythological or allegorical painting.

The live simulation not only enables images to ‘contain [a] world’ once more, but it also replicates the ability of pre-modernist painting to imprison the infinite within a finite surface, and to generate timelessness using an object that exists in time. In paintings, this happens because, as John Berger noted, ‘there is no unfolding time’. [4] All elements are present simultaneously, still and silent: it’s up to the viewer to navigate the surface, home in on the details and connect them in a story, in an act of contemplation that has a beginning, but no intended end. Live simulations achieve a similar result by bringing to life complex systems that can basically go on forever. While the movements of the camera can be programmed in a way that recalls the cinematic experience, guiding the viewer’s eye and not permitting them the free, autonomous exploration possible on a painted surface, the generative behaviour of the environment and the creatures inhabiting it, as well as the infinite duration of the simulation, makes it closer to the experience of a still image than of any time-based medium. In live simulations, infinite duration equals stillness.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Still Life with YumYums, 2016. Live Simulation.

If we accept this parallel between pre-modernist painting and computer-generated live simulations, it comes as no surprise that most live simulations effectively re-enact and build on the classical genres of Western tradition: the still life, the landscape painting, and the historical, religious, mythological or allegorical painting. Still Life with Yumyums (2016), one of Triantafyllidis’ first simulations, explicitly addresses the still life. On a rotating wooden surface, a vibrant, teeming micro-world develops autonomously, inhabited by both inanimate objects – a banana skin, a melted candle, a smartphone, a hamster wheel, some toy weapons – and various colourful, meowing, semi-abstract living creatures. Inspired by a 1994 paper and research by Karl Sims, ‘Evolving Virtual Creatures’, [5] Triantafyllidis designed a number of creatures by joining 3D primitive shapes like cubes and spheres with artificial muscles, then equipping them with DNA that defines their behaviour and leads them to mate and evolve, adapting to their environment. This developing ecosystem is watched over by a flying, sausage-like red worm that attempts to keep the creatures’ behaviour under control, preventing orgies and mating that could result in excessive population growth. Cruel yet playful, childish and obnoxious at the same time, Still Life with Yumyums is a memento mori that takes the form of a fish tank: it places the viewer in ‘God view’ mode, eliciting wonder, amusement, indifference or even horror, and prompting an inevitable analogy with our life on Earth.

Still Life with Yumyums is a memento mori that takes the form of a fish tank.

While the world the Yumyums live in has some order and rules, that constructed in How To Everything (2016) borders on chaos. Various 3D animated objects, each with its own behaviour pattern, appear and disappear in an abstract, otherwise empty environment that changes colour at every cut: falling stones, flying drones, a knife that slices into whatever it finds, a hovering hand that points, waves, glides around, strokes things; a clucking chicken that runs around flapping, trying in vain to take flight.

Theo Triantafyllidis, How to Everything, 2016. Live Simulation.

How To Everything introduces a practice that has become customary in Triantafyllidis’ work: the use of modernist devices and tropes to reveal the artificial nature of the simulation, challenge the viewer’s expectations, and make the generated environment more chaotic and hybrid. Here, the modernist device of cinematic montage fails to generate a consistent narrative by connecting each scene with previous scenes. The background is flat and monochrome, inhabited not just by animated 3D objects and creatures but also by brushstrokes of paint, moving lines and bi-dimensional user interface icons.

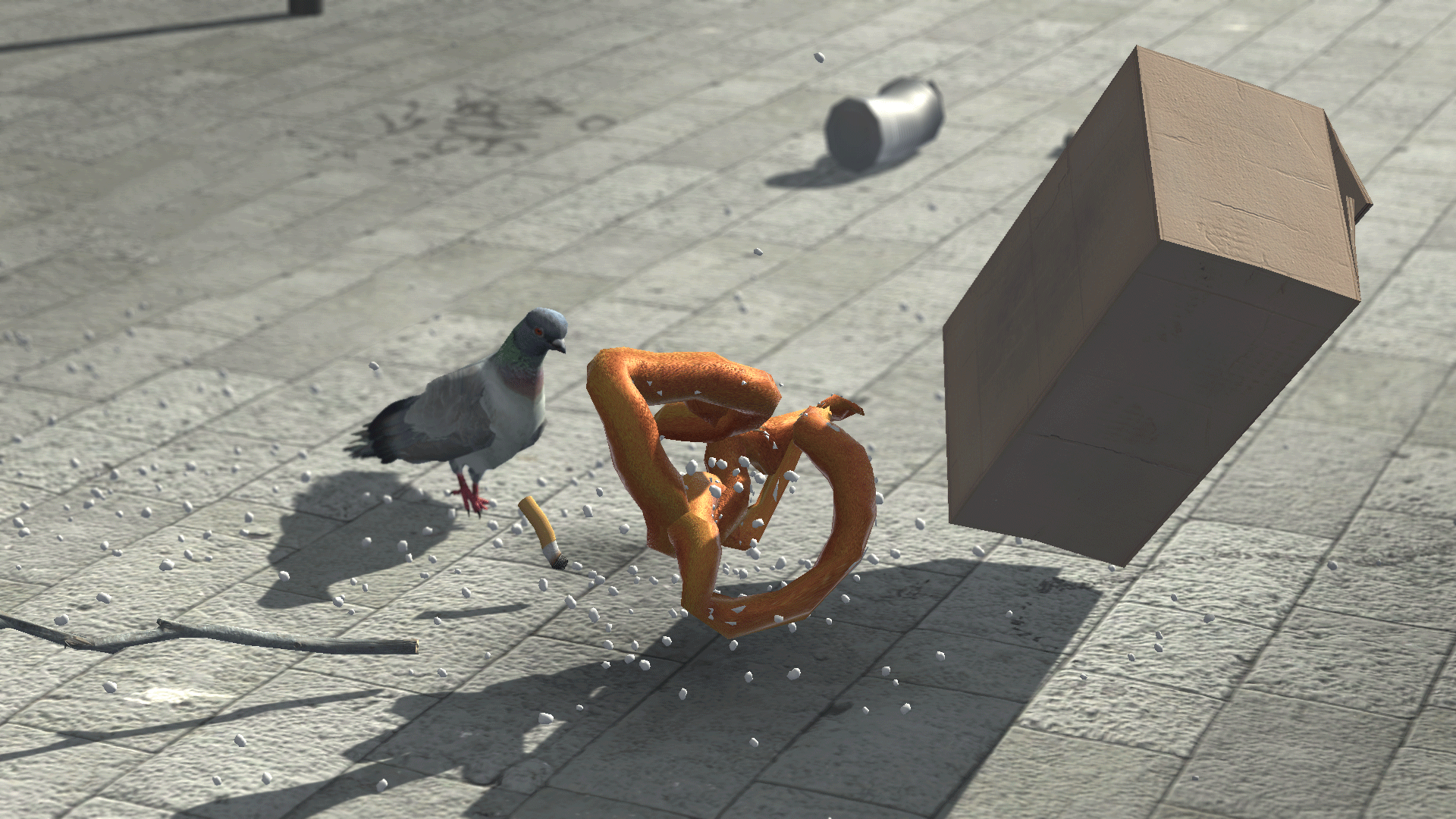

Rejected as sterile conventions in Painting, modernist tools return here and in Triantafyllidis’ subsequent simulations as instruments that say: the world you are looking at is not a representation; it’s a construction. It doesn’t follow reality; it lives by its own rules. Triantafyllidis’ computer-generated worlds are never a reconstruction or a representation of the so-called ‘real’ world, even when they get closer to the kind of photo-realism used in mainstream video games, as happens in Prometheus (2017): the live simulation of a pigeon endlessly and aggressively pursuing a pretzel. Here, everything is realistically emulated, except the pretzel, which moves around autonomously as if it’s a living being, seems to have the rubbery consistency of liver, and never crumbles.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Prometheus, 2017. Live Simulation.

While Prometheus is set in an urban environment, which we experience from the limited point of view of the pigeon, Seamless (2017) is a large landscape simulation that recreates a post-apocalyptic natural environment inhabited by animals (such as bears and deer), giant robots, flying spaceships and the debris of a dead civilisation. No human life is present, but although the work is usually displayed horizontally on three synchronised screens, the viewer’s gaze is somehow included in the environment as an activating element, as happens in virtual reality. In an interview, Triantafyllidis recalls the experience of navigating Google Earth in VR as an inspiration, explaining: ‘The way you navigate and manipulate this 3D model in VR totally changes your relationship with, and perception of, the earth – you feel like the whole planet is an object, but on a different scale.’ [6] This perception is strengthened by the fact that the landscape is actually unfinished, meaning that the blank background emerges here and there, brushstrokes sweep slowly among deer and palms, and transparent mountains with a visible wireframe lie peacefully behind more realistic ones.

The world you are looking at is not a representation; it’s a construction. It doesn’t follow reality; it lives by its own rules.

Three years later, Ritual (2020) picks up the same line of research, but instead of allowing us to lurk and observe the landscape as if it was a painted panorama, it guides the viewer inside the environment, at floor level. Again, the 3D space and the objects and characters that inhabit it are realistic, but the sky is flat and monochrome and painted interventions are visible in almost every scene and on almost every surface. There’s no human presence, but the micro-events of this indefinable ritual are set in a decaying suburban setting that seems to have been recently abandoned, as traces of human activity can still be seen: columns of smoke signal the presence of working factories; machines are still running; two mean hyenas are dancing to the music from a car radio; crows race by on Bird™ scooters; and a colony of ants is picking up and carrying everything from microchips to bottle caps to flowers, and occasionally writing mysterious words on the ground.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Ritual, 2020. Live Simulation.

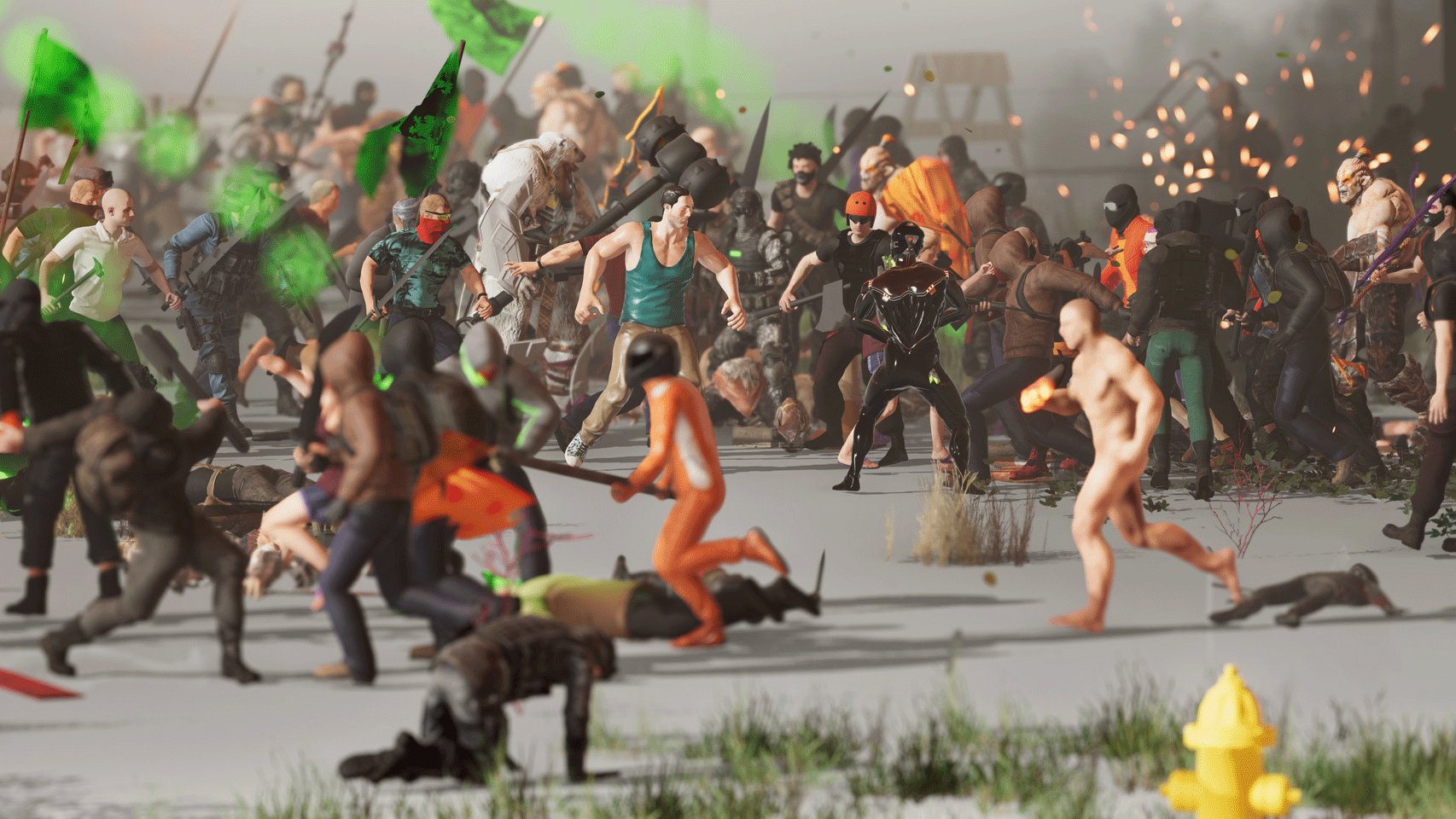

Both the far future of Seamless and the near future of Ritual – which, like the virtual reality of Staphyloculus (2017), is inspired by an actual physical location, 3D-scanned and used to generate the live simulation – preserve the memory of an undisclosed dramatic event in which human life disappeared from Planet Earth. So what happened? One possible answer is offered by Radicalization Pipeline (2021), to date Triantafyllidis’ most direct engagement with current affairs. The title, borrowed from Joshua Citarella’s artistic research and political theory, refers to ‘the algorithmic bias towards extreme content that threw a large number of people down a rabbit hole of political radicalisation on YouTube and various social media platforms’ [7] , the most visible and dramatic consequence of which was the storming of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021. Watching the footage captured by those who took part in the event, the artist was shocked by the ‘other-worldly trance’ [8] that these people seemed to be in, and this was a key source of inspiration for Radicalization Pipeline.

Radicalization Pipeline (2021) is Triantafyllidis’ most direct engagement with current affairs to date.

In the simulation, hordes of dumb non-player characters (NPCs) are engaged in a mass riot: aliens, furries, medieval knights, Orks, protesters, elves, bikers, cops, soldiers, fantasy and futuristic characters, as well as regular Joes holding a range of flags, are running around killing each other with melee weapons. When they die, they sink into the ground and respawn, endlessly. The events unfold in slow motion, set to a soundtrack by the composer and sound designer Diego Navarro that mingles medieval versions of pop songs with the sounds of explosions, gunshots, clashing swords and samples of conversations taken from social media. The images inevitably call to mind battle-scene paintings, as well as the various triumphs of death and the teeming paintings of Bruegel the Elder, as well as war video games. In this work, gaming culture is explicitly addressed as one of the cultural influences thought to affect the process of radicalisation.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Radicalization Pipeline, 2021. Live Simultation.

Although it – unusually – depicts humans, Radicalization Pipeline has a lot in common with Triantafyllidis’ previous simulations. Driven by algorithms – just as we are on social media, both individually and as a group – the mob behaviour of his rioters recalls the simple life of the Yumyums, or the repetitive tasks performed by the ant colony in Ritual. In the worlds constructed by Triantafyllidis, artificial intelligence is always dumb, instinctual, linear, responding to a single imperative: eat, shit, breed, accumulate, fight, kill, survive. His lone heroes are no different: the blind red worm, the chicken, the pigeons, the pretzel, the spaceships, the crowds all do what they are programmed to do, endlessly. Some of them have the task of surveillance, which is also carried out by the viewer: they are the gods of their worlds, sometimes indifferent, sometimes proactive.

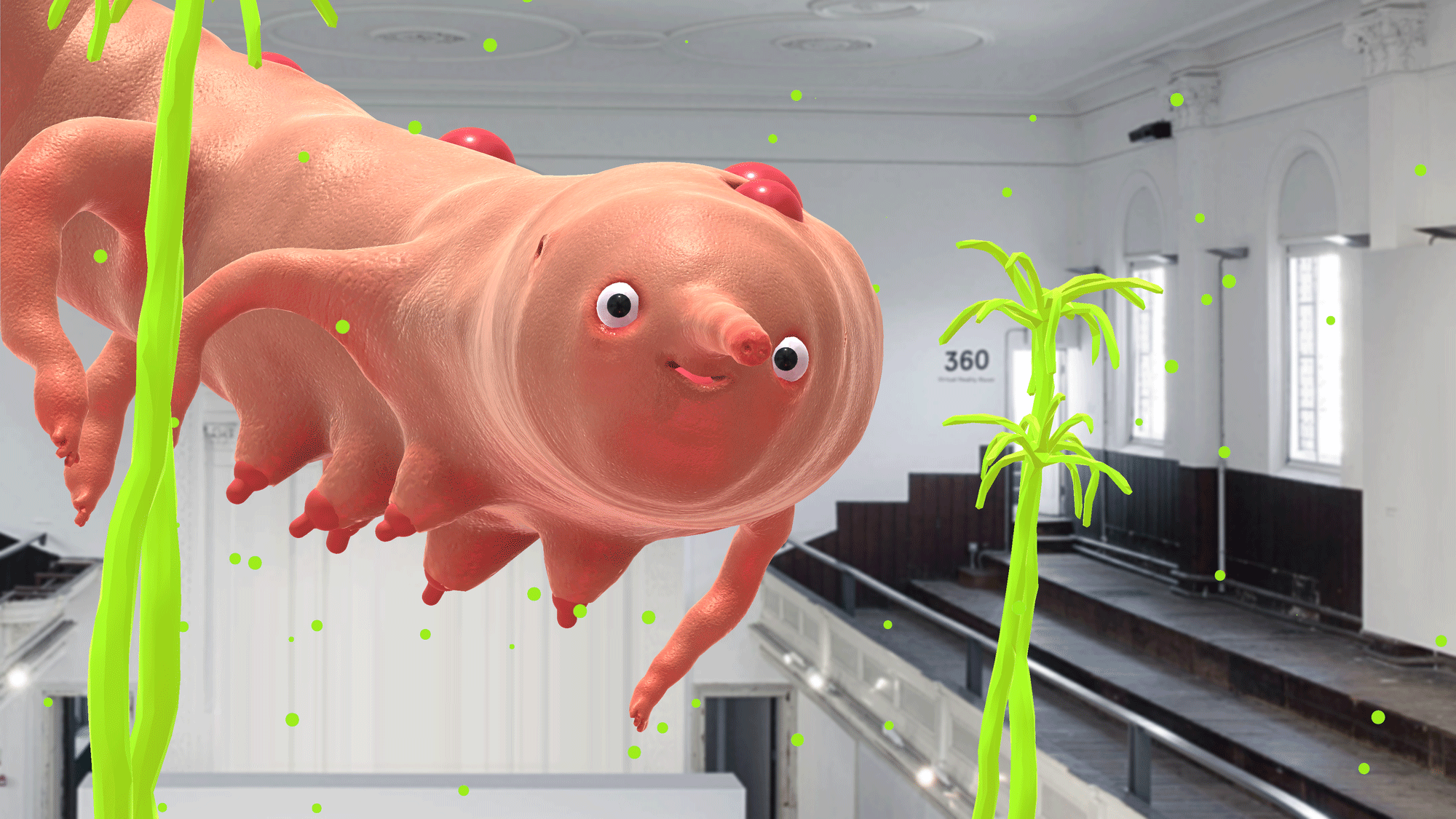

Genius Loci shows us the people inhabiting the space – ourselves included – as Yumyums: dumb creatures busy surviving and evolving, unaware of the laws governing the world we live in.

The best example of this can be seen in Triantafyllidis’ recent AR application, Genius Loci. Conceived as a site-specific application that can be adapted to various environments, Genius Loci allows us to watch a giant pink creature flying around. Like Artemis of Ephesus, the creature has many breasts (a symbol of fertility) that can be milked by the viewer but, rather than following a classical ideal of beauty, its body looks more like a giant worm, sausage or penis. In the artist’s description, it’s ‘arrogant, sexy, snarky, sometimes obnoxious but also cute and lovable’. As it floats around the venue, it shows us the people inhabiting the space – ourselves included – as Yumyums: dumb creatures busy surviving and evolving, unaware of the laws governing the world we live in.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Genius Loci, 2021.

Site Specific Augmented Reality Experience.

[1] Triantafyllidis, Theo, 2018, Painting – Preview. https://vimeo.com/562546985

[2]‘Queering Ork aesthetics & existing beyond the virtual: Theo Triantafyllidis in conversation with Faith Holland’, Aqnb, 23 July 2018. https://www.aqnb.com/2018/07/23/queering-ork-aesthetics-and-existing-beyond-the-virtual-theo-triantafyllidis-in-conversation-with-faith-holland/

[3]Growe, Brend, 2001, Edgar Degas 1834–1917. Cologne: Taschen, p. 10.

[4]Berger, John, 1972, Ways of Seeing – Episode 1. https://youtu.be/0pDE4VX_9Kk

[5]Sims, Karl, 1994, ‘Evolved Virtual Creatures’. https://www.karlsims.com/evolved-virtual-creatures.html and Sims, Karl, 1994, ‘Evolving Virtual Creatures’, Computer Graphics (Siggraph 1994 Proceedings), July, pp. 15–22. https://www.karlsims.com/papers/siggraph94.pdf

[6]‘Talk to me: Eva Papamargariti + Theo Triantafyllidis in dialogue on the entanglement of human, machine + nature’, Aqnb, 31 May 2017. https://www.aqnb.com/2017/05/31/talk-to-me-eva-papamargarititi-theo-triantafyllidis-in-dialogue-on-the-entanglement-of-human-machine-nature/

[7]Bittanti, Matteo, 2021, ‘Theo Triantafyllidis: Radicalization Pipeline’, VRAL. https://milanmachinimafestival.org/vral-theo-triantafyllidis

[8]Bittanti, Matteo, 2021.

Theo Triantafyllidis

Theo Triantafyllidis is an artist who builds virtual spaces and the interfaces for the human body to inhabit them. He creates expansive worlds and complex systems where the virtual and the physical merge in uncanny, absurd and poetic ways. These are often manifested as performances, virtual and augmented reality experiences, games and interactive installations. He uses awkward interactions and precarious physics, to invite the audience to embody, engage with and challenge these other realities.

Through the lens of monster theory, he investigates themes of isolation, sexuality and violence in their visceral extremities. He offers computational humor and AI improvisation as a response to the tech industry’s agenda. He tries to give back to the online and gaming communities that he considers both the inspiration and context for his work by remaining an active participant and contributor.

Theo holds an MFA from UCLA, Design Media Arts and a Diploma of Architecture from the National Technical University of Athens. He has shown work in museums, including the Hammer Museum in LA and NRW Forum in Dusseldorf, DE and galleries such as Meredith Rosen Gallery, the Breeder, Eduardo Secci and Transfer. He was part of Sundance New Frontier 2020, Hyper Pavilion in the 2017 Venice Biennale and the 2018 Athens Biennale: ANTI-. Theo Triantafyllidis is based in Los Angeles.

slimetech.org

Domenico Quaranta

Born 1978, Domenico Quaranta was raised in the countryside and lives in his filter bubble. Since the early 2000s, he has been spending most of his time speaking art and visual culture in front of diverse audiences, curating exhibitions of contemporary artifacts, writing texts and releasing them in the infosphere, enjoying life with his beloved ones and trying to understand the world he's living in. Once a frequent, now erratic collaborator with magazines and reviews, his books include In My Computer (2011), Beyond New Media Art (2013); AFK. Texts on Artists 2011 - 2016 (2016) and Surfing con Satoshi. Arte, blockchain e NFT (Postmedia Books, Milano 2021). He contributed to, edited or co-edited a number of books and catalogues, including Sopravvivenza programmata (2020, with V. Catricalà), GameScenes. Art in the Age of Videogames (2006, with Matteo Bittanti) and THE F.A.T. MANUAL (2013, with Geraldine Juarez). Curated exhibitions include: Holy Fire. Art of the Digital Age (2008); RE:akt! (2009 - 2010); Playlist (2009 - 2010); Collect the WWWorld (2011 – 2012); Unoriginal Genius (2014); Cyphoria (2016); Escaping the Digital Unease (2017 and 2018 - 2019); Hyperemployment (2019 - 2020); For Your Eyes Only (2021). He lectures internationally and teaches “Interactive Systems” at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara. In 2011 he co-founded the now defunct Link Art Center.

domenicoquaranta.com

All artworks courtesy of the artist.