To open this theme of “Fictional Universes”, two guest publishers have joined this second issue of Fabbula.

Fanny Barnabé, from Liège University, writes on video games, namely a dense, brilliantly informed book on narration in video games (english excerpt here), and that in my opinion offers an unprecedented synthesis on what narration does in video games.

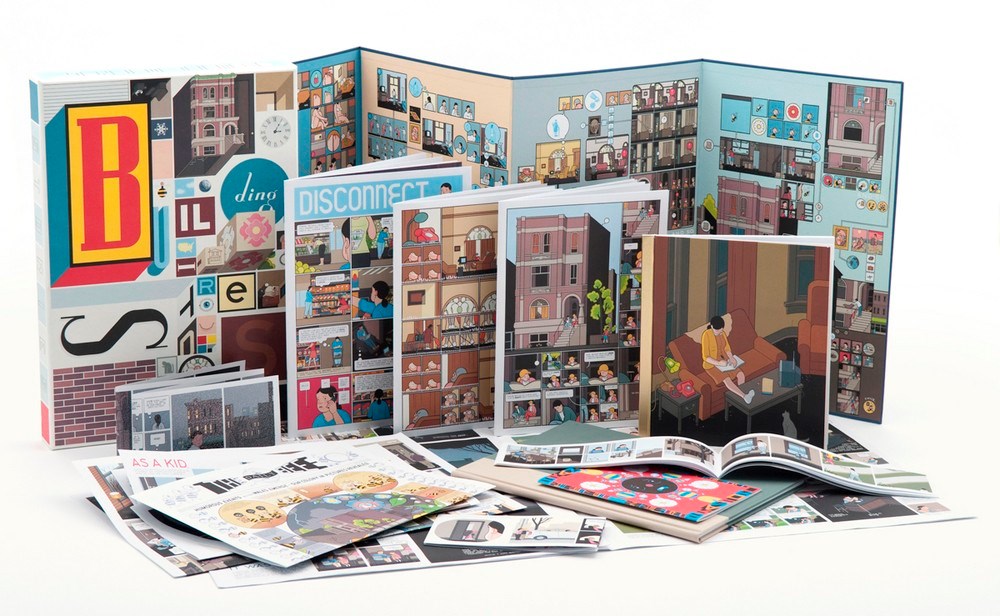

In this book, Barnabé proposes the concept of “Fictional Universes,” or how narration in games is only expressed by the player’s activating multiple elements of narrativisation: thus not only the story and the cinematics, but also the décor, interfaces, camera, interactions, characters, and half a dozen more take part in storytelling. We believe these Fictional Universes to be an ideal starting block for studying the conditions of narration in Virtual Reality, where, there too, stories are only conceived when activated by the spectator who becomes a co-author of the story.

Our travelling companion in our exploration of virtual stories is Paul Sztulman, who comes from the world of contemporary art, and who writes with an inspired, committed pen on video games, their narrative particularities and décors, while mostly ignoring distinctions between disqualified arts and official arts. Paul Sztulman is one of the rare commentators who combine a sharp critical sense with an active personal interest in the practices of games.

This is to say that our conversations were rich in substance and potential exploration targets. Here is the summary and the thinking framework we propose to follow on our peregrinations to come.

Intensification of the field of experience

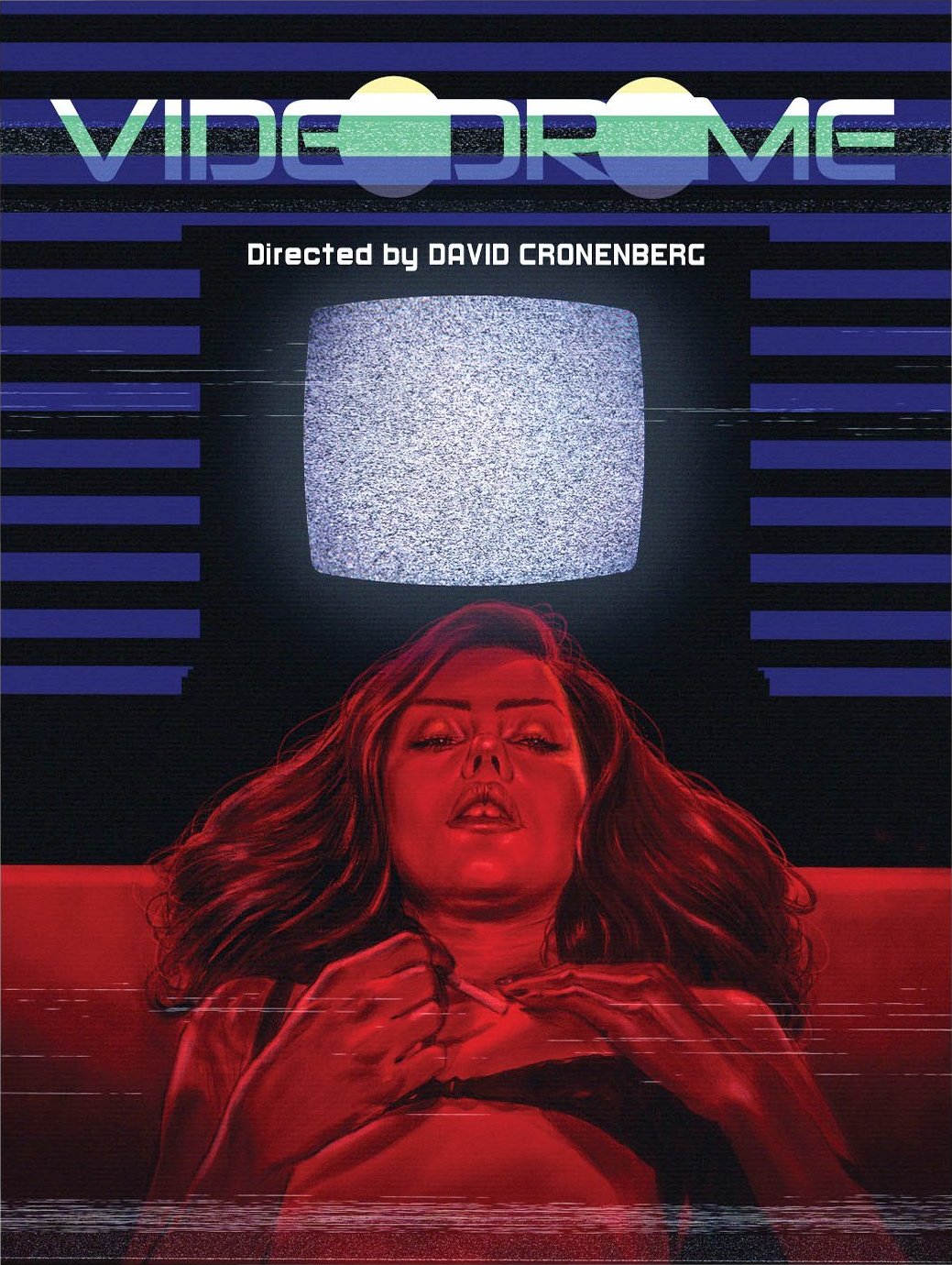

We are all certainly impressed by the immersion procured by Virtual Reality. It deceives our brain and sends us back to our memory as a species. At once, we are presented with a fictive reality, in which our body reacts to fictional stimuli even if “we are not submitted to the perils of what we see,” as Paul reminds us. These very strong affects recall the powerful sensations of horror movies, as well as amusement parks.

We submit that the facility of the triggering of these emotions calls for a reopening of the fields of affects treated in works of virtual reality. Because if powerful sensations and vertiginous affects constitute modern Hollwood’s lucrative business (and maybe the central conditions of its attractiveness), virtual reality achieves similar results with a lot less effects. Could this facility open onto a much larger and more complex range of emotions, such as contemplation, nostalgia and intimacy?

It could also be about intensification of experience. On one hand, even stronger instinctual drive, such as what can be felt when playing DRIFT. On the other, an open field for more reflexive emotions and passive affections.

This brings to mind the contribution of European cinema in the fifties and sixties, that introduced new sensations such as languishment, contempt, desire; the ambiguous, complex emotions of films of a new kind.

We impatiently await the arrival of the Antonioni and Veerasethakul of Virtual Reality! In the meantime, we’ll note and comment on the range of affects we come across during our visual explorations…

The question of the spectator and his representation

Fanny reminds us that if movies give the spectator the camera’s point of view, video games have worked for a long time with multiple points of view (the principle of adjustable cameras and immersive 3D games, etc.). In Virtual Reality, it seems that the point of view and its representation become presence. This opens new conditions for the spectator who accepts Coleridge’s “Willing suspension of belief.”

We make reactions and render presence. Fanny notes that it’s about new combinations between avatars and cameras. The notions of “who am I” and “what am I doing” become central in the narrativity of works of Virtual Reality. For example, you could be a passive, transparent spectator in Felix & Paul’s movie, Wild. In the short-length movie Henry by Oculus Studios, you’re still passive but supposedly visible? In the game Adventure Time, you’re an active character, made visible by the actual characters you control.

In the following weeks, we’ll note the types of combinations into which spectators are plunged and the effects on the narrativity.

Dreams and heterogeneous perceptions; new possibilities of stories

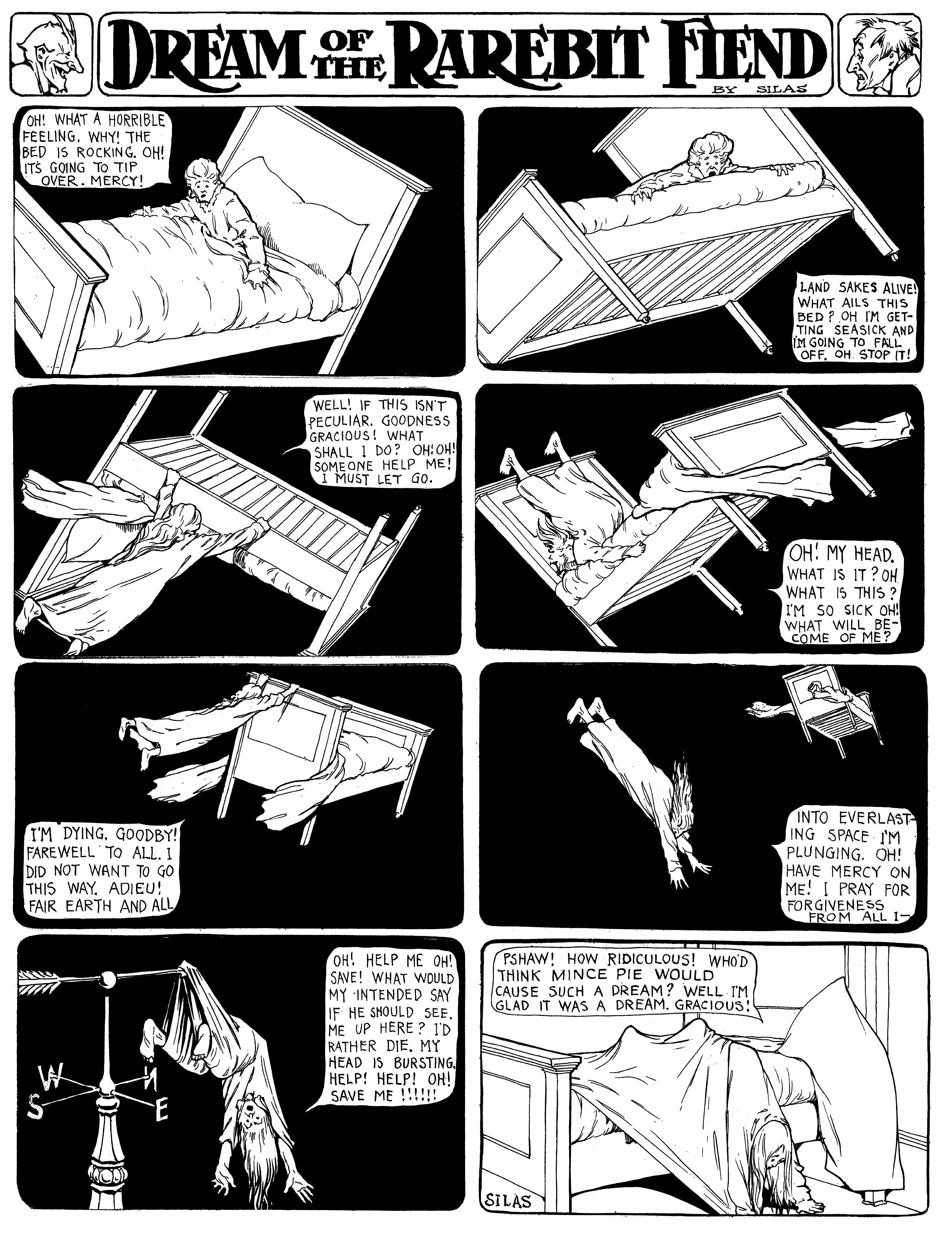

Paul has a very particular domain of inspiration in mind: the field of dreams. He reminds us that in dreams “there is hardly ever perception of one’s own body before oneself (Autoscopy).” One’s vision is always subjective. Cinema, drawing, painting and literature are good at representing dreams. But these mediums rarely favour subjective view, preferring to represent the dreamer in his dream as not to destabilize the reader or viewer, as can be seen in the 800 drawings by Winsor McCay’s Dream of the Rarebit Fiend in 1904. Virtual Reality offers the rarely explored track of adopting the point of view of the dreamer, similar to Wim Wender’s movie Until the End of the World, in which it is possible to record one’s dreams and therefore “see” them and show them to others.

We will also discuss altered perceptions and how Virtual Reality opens new possibilities of expression of heterogeneous points of view, like the work of Marshmallow Laser Feast for animals, as well as the beautiful work on the world of the blind in “Notes on Blindness.”, now a great documentary and soon a VR experience.

Inspiration from synaesthesia will also be a subject to study. Paul reminds us that the origins of the “synthesis of perceptions” and correspondence between the different senses go back to the nineteenth century, when the beginnings of surgery reveal distinct nervous systems and the scientific classification of the “five senses.” Refusing the simplicity and the shortcuts of this rationalization, Baudelaire was first to write on sensorial equivalences and combinations; the foundation of a culture of synaesthesia that inspires many creators of Virtual Reality, such as InnerspaceVR.

The heterogeneous perceptions and connexions between several sensorial networks are at the heart of research offered by Virtual Reality. In the next few weeks we will see how these themes are put into narrative form in the present productions of Virtual Reality.

See you soon on these pages,

Fanny Barnabé, Paul Sztulman, Fabien Siouffi- Fabbula’s Editorial Committee for March 2016 issue